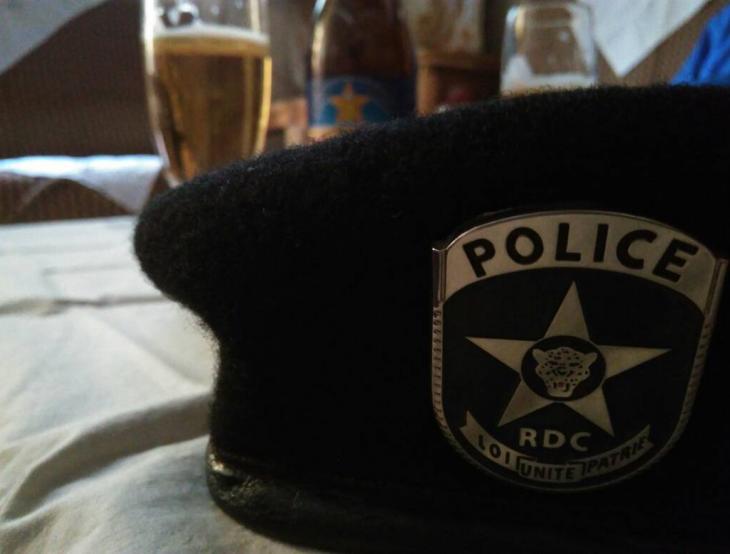

Kuishi kama mbwa ama nguruwe (Living like dogs and pigs): A Bukavu policeman’s lot is not a happy one

by Robert Njangala, Michel Thill, Josaphat Musamba

Introduction

I never wanted to accept that my child sees our way of working. Every time he sees the police’s harassments, he tells me: ‘Daddy, do you do this too? Is that how you work?’ It is shameful and it causes heartache.[1]

It is hard to understand the daily lives of police officers in Bukavu without also considering the difficulties of their personal lives. Up until 2014, reforms gave the police hope for better living conditions. Today, however, this hope has transformed into disappointment and frustration. The private life of a police officer is characterized by growing misery. They speak of the rising costs of housing, food, education for their children and health care. Yet in the face of these difficulties, most of them continue to work, from morning to night, day in day out—but where do they find their motivation?

The poverty of a police officer’s life

We are used to suffering. We do not even know if one day, we will escape this suffering …[2]

A 2013 law defining the status of career police officers guaranteed them several benefits, including family allowance, accommodation assistance and health care. These benefits, however, only exist on paper. Although the philosophy of community policing (‘police de proximité’) encouraged police officers to live among the population, many cannot afford to do so and instead live with their families in Bukavu’s largest police camp, Camp Jules Moké.

For a one-off fee of USD 140, which is payable to the camp’s authorities, police officers can access its housing. Even so, the lack of sanitation, electricity and running water, makes housing conditions difficult. Living in close proximity, quarrels between neighbours and within families are common. One of the camp’s residents reflected: ‘The police officers spend the nights with their families under tarpaulins. Go to Camp Brasserie [Camp Jules Moké], you will see how police officers and their families sleep like pigs...’[3] That is why others decide to live in Bukavu’s outskirts or its peri-urban areas, in small houses, often with two narrow rooms, despite a monthly rent of 20 to 40 dollars.[4]

In a country where women in urban areas give birth to an average of five children,[5] a policeperson’s salary is insufficient to pay for children’s education. Tuition fees can amount to five dollars per child per month. Consequently, a good number of police officers’ children are not schooled and others are chased away from the classroom because their parents did not pay the fees. One police officer explained: ‘We [the police] who have to struggle during a whole month to save this amount, we have to be patient … It makes me suffer, it worries me a lot.’[6] Another alluded to the necessity to make do and be creative: ‘I use my brain to cope with the tuition fees of my children.’[7]

In terms of health care, the police service has established a mutual health care fund, which demands each salaried police officer to contribute a fixed amount according to his or her rank—two dollars for agents and brigadiers; three and a half for sub-commissioners and commissioners; and five and a half for the two highest classes. A team stationed next to the bank counter where police are paid their salaries, collects the payments. The threat of detention means nobody can escape payment. Despite the fund, neither the police officers nor their family members can easily access health care. And those who are not paid do not receive any at all. One police officer compared the fund to a system of extortion: ‘It has become another way to extort money from us only to do nothing. Because even if one fell ill, you arrive there, you just receive three paracetamol pills.’[8]

Finally, there is the need to find food—the police officer’s most urgent daily challenge. Feeding a family of five children can cost five dollars a day. And even if only one daily meal is taken, food costs can consume more than half of the monthly salary. In this context, knowing how to make ends meet is crucial. One policeperson explained: ‘Everything is difficult, everything is difficult. First, eating is like a miracle for us because to be able to eat, we need a lot of acrobatics and often we live the life of beggars.’[9]

The daily pressures police officers are exposed to in their personal lives have serious consequences. On the one hand, survival becomes a justification for harassment and dishonesty: ‘If you keep a dog without feeding him, he will steal. Whether you like it or not, that dog will steal.’[10] On the other hand, this pressure pushes police to turn to alcohol and drugs: ‘Many police officers take drugs because life really gives us too much to worry about.’ [11]

All of these struggles and difficulties damage the reputation of police work to the extent that many discourage their children from choosing a career in policing. If life in the police is so difficult and unappreciated by the population, why do the police continue to work? Where do they find the energy to go on?

Why settle for the police officer’s lot?

It is disgusting, it makes us abandon our work spirit because the authorities neglect us. None of our rights are respected. Now … many among us merely wear their uniform to go and find something for themselves, but they don’t wear it to serve the population.[12]

The difference between the hope and good intentions the police had during the years when reforms were introduced, and the current reality, is stark. During the priod of their training, police officers were reassured by per diems, daily food rations, social care and good working conditions, all of which were inscribed in the 2013 law on the status of the police. Since the premature end of the police reforms in 2014,[13] however, there has been a swift return to daily hardships and informal means of survival.

Nevertheless, police officers go on working. There are several reasons to explain this. Some have not given up hope that the reforms will return and that things will change again for the better. Those who are unpaid believe their superior’s promise that their salary will arrive soon. Others prefer to avoid the shame linked to desertion. And still others say that they have no choice, that in such a hierarchical command structure, they are obliged to obey their superiors despite all the difficulties.[14]

Most of the policepersons mention their ‘love for the country’[15] as a motivating factor. ‘We work for our country,’[16] explained one police officer. Another mentioned the pride associated with serving under the fatherland’s flag.[17]

Finally—and more pragmatically—a police officer represents the state and is a member of one of its security services. A uniform reflects authority, which, in turn, provides opportunities to generate revenue.

Conclusion

One police commander interviewed, emphasized that in the present day DRC police forces, the lack of non-salary benefits for police officers, erodes an efficient command hierarchy, and causes the regression and even disappearance of community policing’s successes.[18] This failing, coupled with the insufficient or non-existent salary pushes police officers to fend for themselves, often with devastating consequences for their everyday work and lives. Frustration and desperation lead to harassment, alcohol abuse and domestic violence. Despite these adverse socio-economic conditions, the police continue to provide services—as limited as they may be. On the one hand, this is done thanks to a range of informal revenue generating practices, which allow the police force and its officers to survive. On the other hand, hope for a better future, the pride to wear a uniform adorned by the Congolese flag and, indeed, the opportunities this gives to find something to eat, motivate the police to take up their work each morning. Even without a salary and despite ‘living like dogs and pigs’, policing thus remains much preferable to unemployment.

[1] Interview with police officer 4, 20 October 2017 (translated from Swahili).

[2] Interview with police officer 7, 29 October 2017 (translated from Swahili).

[3] Interview with police officer 4, 10 November 2017 (translated from Swahili).

[4] Interview with police officer 1, 31 October 2017 (translated from French).

[5] Government of the DRC, 'Deuxième Enquête Démographique et de Santé 2013-2014’, 2014: 71. Accessed 9 December 2017 (https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/SR218/SR218.e.pdf)

[6] Interview with police officer 1, 31 October 2017 (translated from French).

[7] Interview with police officer 4, 10 November 2017 (translated from Swahili).

[8] Interview with police officer 1, 19 October 2017 (translated from French).

[9] Interview with police officer 1, 19 October 2017 (translated from French).

[10] Interview with police officer 4, 10 November 2017 (translated from Swahili).

[11] Interview with police officer 7, 29 October 2017 (translated from Swahili).

[12] Interview with police officer 7, 29 October 2017 (translated from Swahili).

[13] The British-funded Security Sector Accountability and Police Reform (SSAPR) programme ended following excessive violence committed by the police against youth gangs during Operation Likofi (end of 2013–beginning of 2014) in Kinshasa. Yet SSAPR had never financed neither the police units implicated in the operation, nor Kinshasa’s municipal police institution and structure. A damning OHCHR report on this operation can be found online: Accessed 9 December 2017 (http://www.ohchr.org/Documents/Countries/CD/LikofiReportOctober2014_fr.pdf)

[14] Focus Group A, B and C, 2 and 3 November 2017.

[15] Focus Group A, 2 November 2017 (translated from Swahili)

[16] Focus Group B, 2 November 2017 (translated from Swahili)

[17] Focus Group C, 3 November 2017.

[18] Interview with police officer 9, 8 November 2017 (translated from French).

Login or register for free to get all access to our network publications. Members can also connect and discuss with other members. Participate in our network.